After leaving school in Cardiff in 1943, Allen Phillips Griffiths entered University College Cardiff, as it then was, to read History.

So we can say History was his first love.

Enlisted for national service at the end of the war in 1945, Allen Phillips Griffiths was deployed to the Middle East in the Intelligence Corps, eventually returning to Cardiff to complete a degree in Philosophy.

From there Allen Phillips Griffiths went to Oxford, where Herbert Paul Grice was, and where Allen Phillips Griffiths graduated B.Phil in 1953.

His advisor was an author Grice would quote: Price, also from Wales (like Allen Phillips Griffiths, not Grice).

Philllips Griffiths's first academic position was a two year sojourn at the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, from where he moved in 1957 to Birkbeck College, London.

He left Birkbeck with a sturdy admiration, never to be relinquished, for those who managed to combine full time employment with the demands of University study.

So we can say History was his first love.

Enlisted for national service at the end of the war in 1945, Allen Phillips Griffiths was deployed to the Middle East in the Intelligence Corps, eventually returning to Cardiff to complete a degree in Philosophy.

From there Allen Phillips Griffiths went to Oxford, where Herbert Paul Grice was, and where Allen Phillips Griffiths graduated B.Phil in 1953.

His advisor was an author Grice would quote: Price, also from Wales (like Allen Phillips Griffiths, not Grice).

Philllips Griffiths's first academic position was a two year sojourn at the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, from where he moved in 1957 to Birkbeck College, London.

He left Birkbeck with a sturdy admiration, never to be relinquished, for those who managed to combine full time employment with the demands of University study.

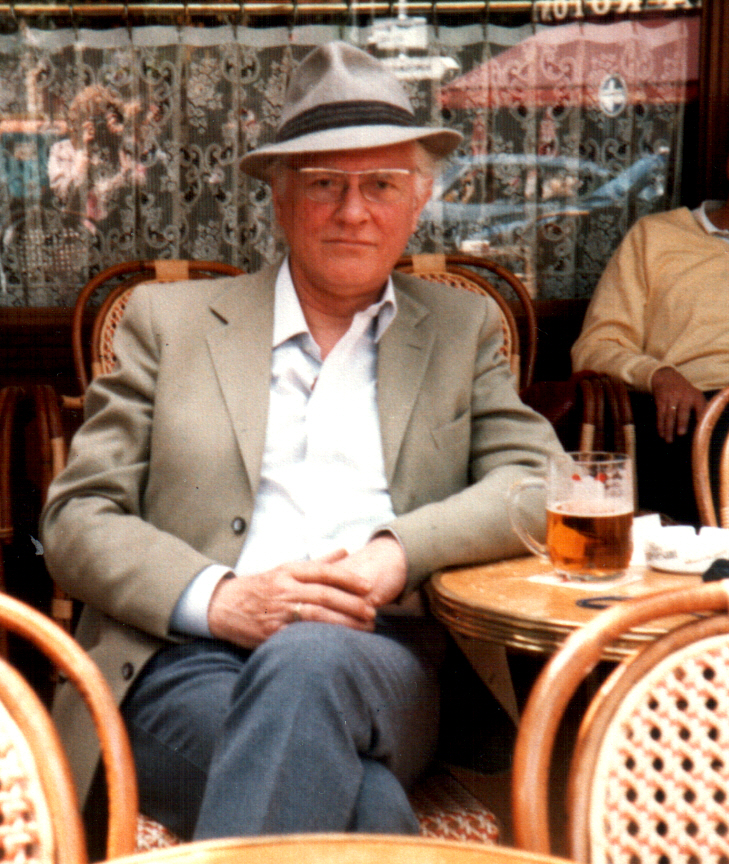

In 1964 Griff was appointed Professor of Philosophy at the newly constituted University of Warwick.

In the ensuing decade he established a strong and eclectic department.

The first member, apart from Griff himself, of "The School of Philosophy", as it was then called (from the Greek 'skhole', meaning 'otium') was Cyril Barrett, a colourful Irish Jesuit priest known principally for his studies in aesthetics, Wittgenstein, and the history of art (especially Irish art and op art), whose donations have considerably enriched the University art collection.

Two other early colleagues were Kit Fine, now Professor of Philosophy at NYU, and Andrew Barker, Professor of Classics at Birmingham, who is widely recognized for his studies in ancient Greek music and musical theory.

In 2005 both Fine and Barker were elected Fellows of the British Academy.

On the occasion of his 50th birthday, nineteen of Allen Phillips Griffiths’s colleagues, friends, and former students conspired in the informal publication of "Griffschrift", a collection whose constituent papers were limited, in principle, to 500 words each.

There is a copy of this mini-Festschrift at B 29.U6 in the University Library, Warwick.

In the ensuing decade he established a strong and eclectic department.

The first member, apart from Griff himself, of "The School of Philosophy", as it was then called (from the Greek 'skhole', meaning 'otium') was Cyril Barrett, a colourful Irish Jesuit priest known principally for his studies in aesthetics, Wittgenstein, and the history of art (especially Irish art and op art), whose donations have considerably enriched the University art collection.

Two other early colleagues were Kit Fine, now Professor of Philosophy at NYU, and Andrew Barker, Professor of Classics at Birmingham, who is widely recognized for his studies in ancient Greek music and musical theory.

In 2005 both Fine and Barker were elected Fellows of the British Academy.

On the occasion of his 50th birthday, nineteen of Allen Phillips Griffiths’s colleagues, friends, and former students conspired in the informal publication of "Griffschrift", a collection whose constituent papers were limited, in principle, to 500 words each.

There is a copy of this mini-Festschrift at B 29.U6 in the University Library, Warwick.

Politically "conservative" (as opposed to socially conservative), Allen Phillips Griffiths had old-fashioned ideas of how to organize an undergraduate curriculum in Philosophy, perhaps under the influence of Grice and Warnock!

Warwick’s Philosophy degree initially contained a substantial amount of history of philosophy, a good deal of ethics, epistemology, and metaphysics, and much more logic than is nowadays fashionable.

There were some options available, including options in Politics, but not many.

To start with there were joint degrees with Politics and with Mathematics -- others were introduced a little later.

A one-year course (what would now be called a module worth 30 CATS) devoted to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason was the centrepiece of the final year of the Philosophy degree.

Allen Phillips Griffiths himself taught this Kant course, as well as the introductory course required of all first-year students, for which he prepared weighty type-written notes devoted to arguments for the existence of God, and to other central topics in traditional metaphysics.

The undergraduate syllabus was of course always in flux.

Being as contrary as he was, Allen Phillips Griffiths did not provoke much surprise, only alarm, with his proposal in the mid-1980s that the Department abandon the teaching of ethics, on the grounds that modern moral philosophy, his own contributions included, was worthless.

Warwick’s Philosophy degree initially contained a substantial amount of history of philosophy, a good deal of ethics, epistemology, and metaphysics, and much more logic than is nowadays fashionable.

There were some options available, including options in Politics, but not many.

To start with there were joint degrees with Politics and with Mathematics -- others were introduced a little later.

A one-year course (what would now be called a module worth 30 CATS) devoted to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason was the centrepiece of the final year of the Philosophy degree.

Allen Phillips Griffiths himself taught this Kant course, as well as the introductory course required of all first-year students, for which he prepared weighty type-written notes devoted to arguments for the existence of God, and to other central topics in traditional metaphysics.

The undergraduate syllabus was of course always in flux.

Being as contrary as he was, Allen Phillips Griffiths did not provoke much surprise, only alarm, with his proposal in the mid-1980s that the Department abandon the teaching of ethics, on the grounds that modern moral philosophy, his own contributions included, was worthless.

Allen Phillips Griffiths’s contributions in the wider philosophical world included a couple of dozen shrewd and well received essays in moral philosophy and in epistemology, and the successful collection "Knowledge and Belief" (1967), edited under the general supervision of G. J. Warnock, later Vice-Chancelor of Oxford, and one of the gems of Grice's "Saturday Mornings"..

The ‘expected and projected major monograph’, according to one of his colleagues, was sunk by ‘his scrupulous self-criticism’ -- and this he shared with Grice.

In 1979 Allen Phillips Griffiths was appointed Director of the Royal Institute of Philosophy, a post he held for fifteen years, and in which he was succeeded by his former student Anthony O’Hear.

His directorship of the R. I. P. (not Rest In Peace, but Royal Institute of Philosophy) was marked by several innovative efforts to bring philosophy out of the academy, as well as by a string of edited volumes, to which he himself usually contributed, containing a printed record of the Institute’s annual lecture series.

A good public speaker, Griff was the first University Orator, and for several years single-handedly presented to the Chancellor all candidates for honorary degrees.

In those days he was perhaps the most sociable and socially active professor in the University.

He was regularly (and frequently) in attendance at "The Six O’Clock Club" (which met at five-thirty), a small group that met on weekdays at Frank’s Bar to assuage the cares of the day with Worthington bitter (priced at 1/11d a pint).

He spent many hours at Frank's Bar (owned by one Frank) talking with undergraduates.

He was the leading voice, as well as chorus master and songwriter, for the School of Philosophy Male Voice Choir, an otherwise inaudible ensemble that was mobilized on three or four occasions as a cabaret act at University social functions.

"Inaudible" is Berkeleyan.

Even those who were not at Warwick in the 1970s may appreciate the prescience of the quatrain

to the tune of Twinkle twinkle little bat.

Academic Registrar

Meteoric rising star

When we come to park our car

How we wonder what you are!

that formed part of a hymn specially written for one of the Choir’s engagements, in Eb.

When he was appointed a Pro Vice Chancellor in 1970, he was a natural choice as Chairman of the Social Policy Committee.

It was under his leadership that the decision was made to revoke the plan to use S&D2 [the second stage of the Social & Dining facilities] as a combined social building for all sections of the University (students, support staff, academic staff, or members of the JCR, MCR, and SCR, as they were then called), and to hand it over in its entirety to the Students’ Union.

Many staff soon began to appreciate the advantage of not housing the Staff Club on the top floor of what is now the main Union Building.

In those days he was perhaps the most sociable and socially active professor in the University.

He was regularly (and frequently) in attendance at "The Six O’Clock Club" (which met at five-thirty), a small group that met on weekdays at Frank’s Bar to assuage the cares of the day with Worthington bitter (priced at 1/11d a pint).

He spent many hours at Frank's Bar (owned by one Frank) talking with undergraduates.

He was the leading voice, as well as chorus master and songwriter, for the School of Philosophy Male Voice Choir, an otherwise inaudible ensemble that was mobilized on three or four occasions as a cabaret act at University social functions.

"Inaudible" is Berkeleyan.

Even those who were not at Warwick in the 1970s may appreciate the prescience of the quatrain

to the tune of Twinkle twinkle little bat.

Academic Registrar

Meteoric rising star

When we come to park our car

How we wonder what you are!

that formed part of a hymn specially written for one of the Choir’s engagements, in Eb.

When he was appointed a Pro Vice Chancellor in 1970, he was a natural choice as Chairman of the Social Policy Committee.

It was under his leadership that the decision was made to revoke the plan to use S&D2 [the second stage of the Social & Dining facilities] as a combined social building for all sections of the University (students, support staff, academic staff, or members of the JCR, MCR, and SCR, as they were then called), and to hand it over in its entirety to the Students’ Union.

Many staff soon began to appreciate the advantage of not housing the Staff Club on the top floor of what is now the main Union Building.

Griff was a heavy smoker at a time when smoking was an acceptable occupation, but he eventually abandoned the habit, settling instead for a permanent diet of snuff, for which he had long had a liking, and in celebration of which, in later years, he maintained a web site.

He collected snuffboxes, and also antique clocks -- perhaps from his days at the Five-Thirty Club.

Music was one of his principal diversions.

He was an enthusiastic poker player, but rarely took arduous physical exercise.

For many years after his retirement in 1992 he neither saw nor corresponded with his former colleagues, but more recently he was coaxed back to occasional companionship, and some of us found considerable pleasure in visiting him again and reviving our friendship with him.

Hardly less sharp-witted than he had ever been, he was as outrageous and opinionated as he had always been, but that was part of his charm.

Our sympathy goes to his son John, to the rest of his family, and to all those who were positively affected by him.

He will be greatly missed.

He collected snuffboxes, and also antique clocks -- perhaps from his days at the Five-Thirty Club.

Music was one of his principal diversions.

He was an enthusiastic poker player, but rarely took arduous physical exercise.

For many years after his retirement in 1992 he neither saw nor corresponded with his former colleagues, but more recently he was coaxed back to occasional companionship, and some of us found considerable pleasure in visiting him again and reviving our friendship with him.

Hardly less sharp-witted than he had ever been, he was as outrageous and opinionated as he had always been, but that was part of his charm.

Our sympathy goes to his son John, to the rest of his family, and to all those who were positively affected by him.

He will be greatly missed.