Cesare Bonesana-Beccaria, Marquis of Gualdrasco and Villareggio[1] (Italian: [ˈtʃeːzare bekkaˈriːa]; 15 March 1738 – 28 November 1794) was an Italian criminologist,[2] jurist, philosopher, and politician, who is widely considered as the most talented jurist[3] and one of the greatest thinkers of the Age of Enlightenment. He is well remembered for his treatise On Crimes and Punishments (1764), which condemned torture and the death penalty, and was a founding work in the field of penology and the Classical School of criminology. Beccaria is considered the father of modern criminal law and the father of criminal justice.[4][5][6]

According to John Bessler, Beccaria's works had a profound influence on the Founding Fathers of the United States.[7]

Birth and education

Born in Milan on 15 March 1738, Beccaria received his early education in the Jesuit college at Parma. Subsequently, he graduated in law from the University of Pavia in 1758. At first he showed a great aptitude for mathematics, but studying Montesquieu(1689–1755) redirected his attention towards economics. In 1762 his first publication, a tract on the disorder of the currency in the Milanese states, included a proposal for its remedy.[8]

In his mid-twenties, Beccaria became close friends with Pietro and Alessandro Verri, two brothers who with a number of other young men from the Milan aristocracy, formed a literary society named "L'Accademia dei pugni" (the Academy of Fists), a playful name which made fun of the stuffy academies that proliferated in Italy and also hinted that relaxed conversations which took place in there sometimes ended in affrays. Much of its discussion focused on reforming the criminal justice system. Through this group Beccaria became acquainted with French and British political philosophers, such as Hobbes, Diderot, Helvétius, Montesquieu, and Hume. He was particularly influenced by Helvétius.[9]

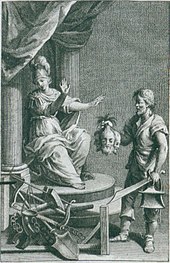

On Crimes and Punishments

In 1764, with the encouragement of Pietro Verri, Beccaria published a brief but justly celebrated treatise On Crimes and Punishments. Some background information was provided by Pietro, who was in the process of authoring a text on the history of torture, and Alessandro Verri was an official at a Milan prison had first hand experience of the prison's appalling conditions. In this essay, Beccaria reflected the convictions of his friends in the Il Caffè (Coffee House) group, who sought to cause reform through Enlightenment discourse.

Beccaria's treatise marked the high point of the Milan Enlightenment. In it, Beccaria put forth some of the first modern arguments against the death penalty. His treatise was also the first full work of penology, advocating reform of the criminal law system. The book was the first full-scale work to tackle criminal reform and to suggest that criminal justice should conform to rational principles. It is a less theoretical work than the writings of Hugo Grotius, Samuel von Pufendorf and other comparable thinkers, and as much a work of advocacy as of theory.

The brief work relentlessly protests against torture to obtain confessions, secret accusations, the arbitrary discretionary power of judges, the inconsistency and inequality of sentencing, using personal connections to get a lighter sentence, and the use of capital punishment for serious and even minor offences.

Almost immediately, the work was translated into French and English and went through several editions. Editions of Beccaria's text follow two distinct arrangements of the material: that by Beccaria himself, and that by French translator Andre Morellet (1765) who imposed a more systematic order to Beccaria's original text. Beccaria opens his work describing the great need for reform in the criminal justice system, and he observes how few studies there are on the subject of such reform. Throughout his work, Beccaria develops his position by appealing to two key philosophical theories: social contract and utility. Concerning the social contract, Beccaria argues that punishment is justified only to defend the social contract and to ensure that everyone will be motivated to abide by it. Concerning utility (perhaps influenced by Helvetius), Beccaria argues that the method of punishment selected should be that which serves the greatest public good.

Contemporary political philosophers distinguish between two principal theories of justifying punishment. First, the retributive approach maintains that punishment should be equal to the harm done, either literally an eye for an eye, or more figuratively which allows for alternative forms of compensation. The retributive approach tends to be retaliatory and vengeance-oriented. The second approach is utilitarian which maintains that punishment should increase the total amount of happiness in the world. This often involves punishment as a means of reforming the criminal, incapacitating him from repeating his crime, and deterring others. Beccaria clearly takes a utilitarian stance. For Beccaria, the purpose of punishment is to create a better society, not revenge. Punishment serves to deter others from committing crimes, and to prevent the criminal from repeating his crime.

Beccaria argues that punishment should be close in time to the criminal action to maximise the punishment's deterrence value. He defends his view about the temporal proximity of punishment by appealing to the associative theory of understanding in which our notions of causes and the subsequently perceived effects are a product of our perceived emotions that form from our observations of a causes and effect occurring in close correspondence (for more on this topic, see David Hume's work on the problem of induction, as well as the works of David Hartley). Thus, by avoiding punishments that are remote in time from the criminal action, we are able to strengthen the association between the criminal behavior and the resulting punishment which, in turn, discourages the criminal activity.

For Beccaria when a punishment quickly follows a crime, then the two ideas of "crime" and "punishment" will be more closely associated in a person's mind. Also, the link between a crime and a punishment is stronger if the punishment is somehow related to the crime. Given the fact that the swiftness of punishment has the greatest impact on deterring others, Beccaria argues that there is no justification for severe punishments. In time we will naturally grow accustomed to increases in severity of punishment, and, thus, the initial increase in severity will lose its effect. There are limits both to how much torment we can endure, and also how much we can inflict.

Beccaria touches on an array of criminal justice practices, recommending reform. For example, he argues that dueling can be eliminated if laws protected a person from insults to his honor. Laws against suicide are ineffective, and thus should be eliminated, leaving punishment of suicide to God. Bounty hunting should not be permitted since it incites people to be immoral and shows a weakness in the government. He argues that laws should be clear in defining crimes so that judges do not interpret the law, but only decide whether a law has been broken.

Punishments should be in degree to the severity of the crime. Treason is the worst crime since it harms the social contract. This is followed by violence against a person or his property, and, finally, by public disruption. Crimes against property should be punished by fines. The best ways to prevent crimes are to enact clear and simple laws, reward virtue, and improve education.

Three tenets served as the basis of Beccaria's theories on criminal justice: free will, rational manner, and manipulability. According to Beccaria—and most classical theorists—free will enables people to make choices. Beccaria believed that people have a rational manner and apply it toward making choices that will help them achieve their own personal gratification.

In Beccaria’s interpretation, law exists to preserve the social contract and benefit society as a whole. But, because people act out of self-interest and their interest sometimes conflicts with societal laws, they commit crimes. The principle of manipulability refers to the predictable ways in which people act out of rational self-interest and might therefore be dissuaded from committing crimes if the punishment outweighs the benefits of the crime, rendering the crime an illogical choice.

No comments:

Post a Comment